The story begins with the Karankawa, the first islanders, and ends with the final extension of our jetties and dredging of a harbor for Port Aransas in 1919. The cast includes Spanish explorers, early ‘Texians’, and the armies of three warring nations.

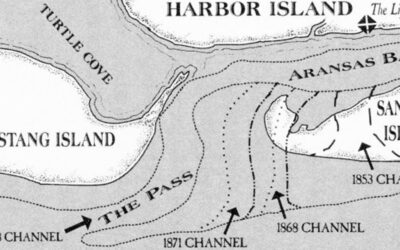

Prior to being tamed, the channel moved southward at a rate of over 200′ per year. Arresting this steady migration was going to require skill, vision, money and determination. It took over fifty years and five attempts before final success. Both private and government groups weighed in before the task was completed.

A railroad the length of the proposed jetty had to be built out into the sea to accomplish this job. A steam locomotive, crane, pile driver and flat cars full of rock had to be transported by barge to the construction site. After the rocks were dumped into the sea the cars had to be returned by barge and traded for loaded ones. The job required tons of dynamite, thousands of trees, millions of pounds of stone and more than a hundred laborers.

The Pass: A Route to Sustenance

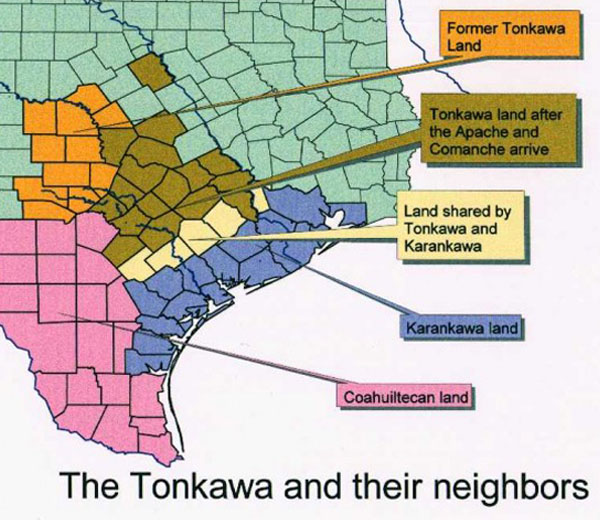

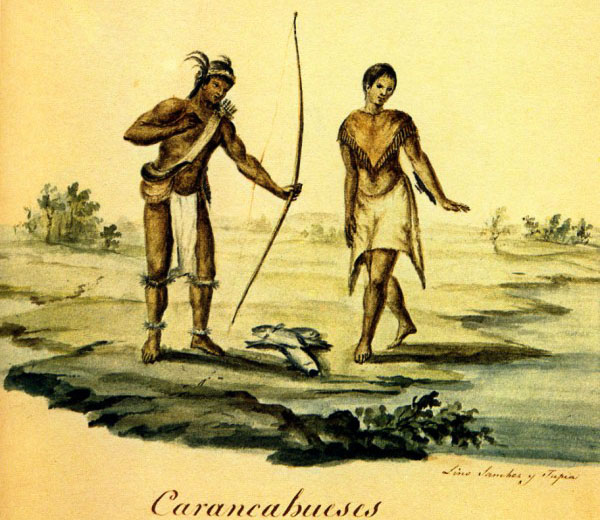

Long before Spanish and French explorers sailed along the Texas coastline indigenous peoples, the Karankawa, claimed the lands from Galveston to Corpus Christi Bay as their own. Nomadic by necessity, the Karankawa migrated with the seasons following the food sources.

Fall and winter offered the bounties of the inshore waters such as redfish, oysters and turtles, while spring and summer required the skill of a hunter to kill bison and deer found inland. Karankawa families traveled in small dugout canoes to move between their summer and winter homes. Roots, nuts and fruits gathered during the inland stay rounded-out the Karankawa diet.

The nomadic Karankawa claimed the lands from Galveston to Corpus Christi Bay as their own.

Karankawa Indians of the Gulf Coast. Watercolor by Lino Sánchez y Tapia.

The Journey of Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca (1542)

“To this island we gave the name of the Island of Ill-Fate. The people on it are tall and well formed, they have no other weapons than bows and arrows with which they are most dexterous. The men have one of their nipples perforated from side to side and sometimes both; through this hole is thrust a reed as long as 2 ½ hands as thick as 2 fingers; they also have the under lip perforated and a piece of cane in it as thin as the ½ of a finger. The women do the hard work. People stay on this island from October till the end of February, feeding on the roots I have mentioned taken from under the water in November and December. They have channels made of reeds and get fish only during that time, afterwards they subsist on roots. At the end of February they remove to other parts in search of food, because the roots begin to sprout and are not good any more.”

The Pass: A Route to Exploration

The Spanish

Wealth, power and fame enticed Spanish exploration away from the Caribbean colonies to the American mainland in the early 16th century. Alonso Alvarez de Piñeda set sail from Jamaica, intending to sail east around Florida. Strong winds forced his fleet of four ships to change course and sail west into unknown waters. In 1519 Piñeda sailed into the Aransas Pass and named the bay Corpus Christi.

Running along the Gulf Coast from the Florida Keys to southern Mexico, Piñeda noted rivers and inlets along the way, creating the first map of the region.

The French

More than a century later, French ships entered the Gulf. With the backing of King Louis XIV, René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle left the port of La Rochelle, France in 1684 with plans of wedging a French settlement between Spanish holdings in Texas and Florida. La Salle’s flotilla consisted of four ships laden with the necessary men and provisions for the French to stake their claim. The expedition ended in death, misery and failure; the Gulf of Mexico remained Spanish waters.

**In 1995 Texas Historical Commission archeologists discovered La Salle’s ship the Belle in Matagorda Bay. Artifacts from this famous ship can be viewed at the Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History and the Texas Maritime Museum in Rockport.

The Pass: A Route to Settlement

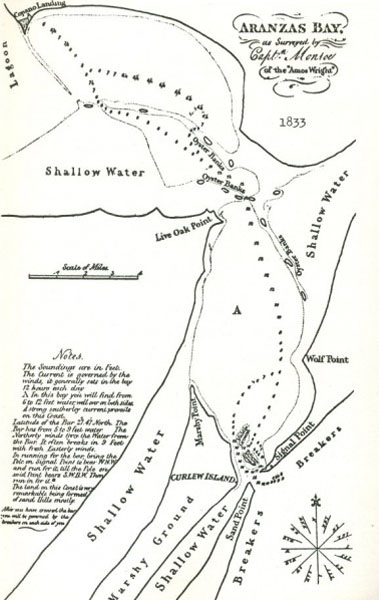

The shallow, narrow pass that connects the Gulf of Mexico to inland waterways was a necessary feature to get goods and people onto the isolated central Texas coast. But the constant movement of this natural channel often led to maritime disasters, especially when combined with rough seas. An 1834 account describes such a journey:

“We arrived at the pass, which we found stormy and bad. Notwithstanding the dangers of trying to cross the bar, the captain announced his determination to enter at any hazard. As our little schooner reached the bar, a rough sea broke on her, and a heavy swell threw her from the channel and she became unmanageable …. Another heavy sea struck her … [lifting] the vessel into shallow water, where she was permanently fixed.” John Linn

Three centuries of exploration proved the importance of the pass, resulting in more accurate charts, but failed to harness or tame this important waterway.